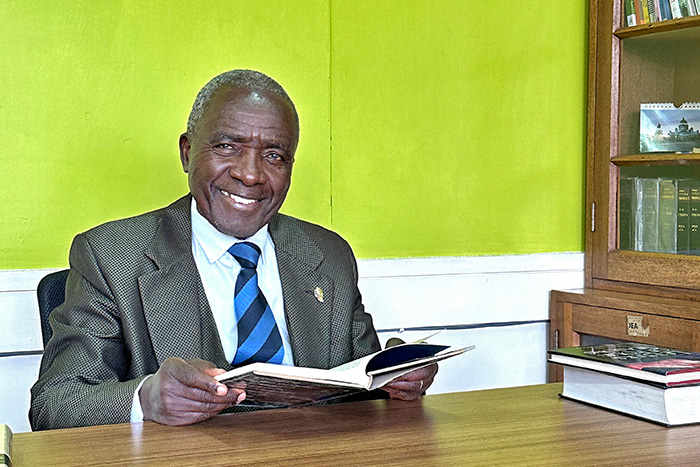

Interview with Professor Henry Indangasi

October 25, 2024

[The following is excerpted from an interview with Professor Henry Indangasi, a renowned literary scholar, conducted by the Seikyo Shimbun and published in the paper on October 25, 2024. Professor Indangasi previously held an in-depth dialogue with Daisaku Ikeda on the significance of world literature. In this interview, he reflects on the evolving role of literature in shaping the future of global society.]

Professor Henry Indangasi

Seikyo Shimbun: As we enter the 2020s, it has begun to feel as though humanity is once again facing the kinds of crises we thought we left in the past—pandemics and war. In such times, some may question whether literature holds any real power. Yet you have declared, “Poetry is life” and “Literature is life.” What drives your passionate commitment to reviving print culture?

Professor Henry Indangasi: Like you, I am deeply shocked by what is happening around the world today. In response to the question of what role literature can play in such circumstances, I would say this: literature deepens and expands our capacity for empathy—the ability to step into the shoes of our fellow human beings. The quality of empathy enables us to see the world from another person’s perspective and to seek and understand their story.

Among those who engage in literature, it is often said that “our enemy” is that person whose story we do not yet know.

All forms of literature affirm values that unite humanity as one family. One of those values is peaceful coexistence. I feel that those who take up arms to kill others have not read great works of literature, nor have they internalized the values found in such works.

Seikyo: You have praised Mr. Ikeda’s The New Human Revolution as one of the ten greatest novels in the world for its role in reviving the essence of humanism in literature. What do you see as the significance of this work in today’s turbulent times?

Indangasi: I first read The New Human Revolution in English 24 years ago. At that time, I became firmly convinced that this novel succeeds in restoring the essence of humanism to literature, which I felt was in danger of being lost as the 20th century transitioned into the 21st century.

The novel vividly portrays moving human interactions. I was deeply touched by the way the characters influence one another. It is filled with profound compassion that teaches the dignity and value of human life. No matter where one is from in the world, readers can see themselves in the characters and, in doing so, elevate their sense of life’s value. This reminds me of the world’s greatest literary works.

That is precisely why I have placed The New Human Revolution among what I consider to be the ten greatest novels in the world.

Great literature speaks to the universal aspects of our shared humanity. From Shakespeare over 400 years ago to Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, the greatest writers have passionately explored the vital relationship between the individual and the broader society.

I believe that Dr. Ikeda’s The New Human Revolution not only reaffirms the moral foundation of world literature, but also illuminates a bright path forward for the future of humankind.

Seikyo: In the early 1990s, the University of Nairobi awarded Mr. Ikeda an honorary doctorate of letters. We understand that it was one of his poems that became the key factor in the selection committee’s decision.

Indangasi: A few days before I attended the university’s Honorary Degrees Committee meeting, I had come across Dr. Ikeda’s poem about Nelson Mandela, “Banner of Humanism, Path of Justice.”

When I read this poem, I felt that he deeply knows the heart of Africa.

A number of poets have composed poems about this iconic leader, Mandela. But they focused more on the racial dimension—how the apartheid regime, led by whites, imprisoned a Black man fighting for racial equality. Daisaku Ikeda’s poem was different. It captured the universal character of Mandela’s persona.

In the poem, Dr. Ikeda writes:

The clouds that gather and cover the sky

cannot conceal the rays of the brilliant sun.

Even with your body fettered

your unbending spirit

was beyond the power of any man

to subdue.

* * *

The great scale of your being

causes even your enemies

to admire and praise you.

The depth of your life

embraces all people.

The brilliant light

of your love for humankind

gently yet powerfully illuminates

the supreme entity

pulsing in the lives of all people.

I had not thought that Japanese people could truly sympathize with the racial discrimination faced in Africa. But this poem changed my attitude.

When I showed this poem to the then vice chancellor of the university, he asked me to make copies for all the members of the committee. He then gave me a chance to address the significance of this poem at the meeting.

University professors are known to be difficult to convince when it comes to intellectual arguments. I know this because I am one of them. But this time, there wasn’t a single opposition. We unanimously agreed to award the honorary doctorate of letters to Dr. Ikeda.

Meeting between Professor Indangasi and Mr. Ikeda (Hachioji, Tokyo, July 2000)

Seikyo: Mr. Ikeda has consistently advocated for dialogue, even in times of conflict, encouraging both world leaders and citizens to engage in conversation. Given Africa’s rich tradition of oral literature and spoken culture, do you feel there is a natural appreciation for the power of dialogue on the African continent?

Indangasi: Since April 2000, I have had the opportunity to teach at Soka University in Japan as part of a faculty exchange program with the University of Nairobi. During my time there, I was deeply moved by Dr. Ikeda’s heartfelt and compassionate dialogues. I strongly believe that in today’s world, we must reinstate a “culture of dialogue.” We should not engage in discussion merely for the sake of argument. After all, the person we are speaking with is not an enemy.

In Africa, conflicts have traditionally been resolved through discussions among village elders until a consensus was reached. Even on delicate issues such as land ownership, marriage, domestic violence and even murder, the goal was always to achieve agreement, rather than to punish or blame.

There were no “winners” in dialogue because to win means to create an enemy. Elders often tapped into the resources of folklore and wisdom of their ancestors to reinforce their perspectives, engaging in discussions over and over again until consensus was achieved.

These meetings, known as barazas in Swahili, were platforms for exchanging views about issues affecting the community. They were a dialogue, often tapping into the resources of our folklore, the wisdom of our ancestors. They were not about creating enemies but resolving conflicts and restoring peace and harmony.

Seikyo: Mr. Ikeda emphasized the importance of learning from Africa, calling it the key to initiating global change and ushering in a new dawn of humanism. Engaging with African culture is essential for young people in Japan and beyond.

Indangasi: Africa is a vast continent home to over one billion people, with more than 2,000 languages spoken—comprising nearly a third of the world’s languages. Each of these languages carries a rich heritage of oral literature.

The literary landscape of Africa is equally diverse, with figures such as Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of Senegal and a renowned poet, as well as Wole Soyinka of Nigeria, the first African writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

I believe engaging with such diverse cultures is incredibly important. In fact, since the spring of 2003, the University of Nairobi has offered courses on Japanese literature, including the works of Dr. Ikeda, to deepen students’ understanding of Japanese culture.

One student who took this course was so inspired by Dr. Ikeda’s writings and Japanese literature that they later became a professor at another university.

Seikyo: In October 1990, during his initial meeting with Nelson Mandela, Mr. Ikeda stated, “Even if South Africa has in you, Mr. Mandela, an extraordinary leader, unless others develop into capable individuals and actively contribute, your work (of the transformation and self-reliance of your country) will remain incomplete.” He then pledged support for education. Professor Indangasi, could you share your thoughts on the significance of education and the power of literature in forging a hopeful future?

Indangasi: I am deeply concerned about the younger generation’s growing disinterest in reading. When I visit university libraries, I see students completely absorbed in their smartphones, paying no attention to the books right before them. These books are waiting to be read.

In today’s world, I am also concerned about the relationship between artificial intelligence (AI) and human beings. For example, AI can now compose essays for students without them having to read a book.

This is precisely why interacting with actual books is so important. Without doing so, one cannot exercise one’s mind.

When I had the opportunity to meet Dr. Ikeda, I was struck by his profound knowledge and insight. I was amazed at how many books he had read to cultivate such an exceptional humanity.

I sincerely hope those who do not have the habit of reading develop a culture of reading within themselves. I especially want young people to encounter great works of literature. By identifying with the characters in a story, they can deepen and enrich their own lives.

To overcome the divisions in today’s society and move toward harmony and coexistence, we need the power of humanity and spirituality more than ever. I believe that the path to cultivating this humanity lies in the role of literature and poetry, something that Dr. Ikeda consistently emphasized.

Henry Indangasi is Professor Emeritus at the University of Nairobi. Born in Kenya in 1947, he served as the chair of the university’s Department of Literature for five terms, beginning in 1984. In April 2000, he spent six months as a visiting professor at Soka University in Japan. He has also served as chair of the Writers’ Association of Kenya for many years. Professor Indangasi’s dialogue with Daisaku Ikeda is compiled in the Japanese book Sekai no bungaku o kataru (English translation: Dialogue on World Literature), which was published in 2001 by Ushio Publishing in Japan.

Share this page