Interview with Professor Stuart Rees

May 2, 2025

[The following is excerpted from an interview with Stuart Rees, professor emeritus at the University of Sydney in Australia, conducted by the Seikyo Shimbun and published on May 2, 2025. In the interview, Prof. Rees reflects on his encounter with Daisaku Ikeda and shares his insights on the ethical foundations required for building a just and lasting peace in today’s world. This version contains additional remarks not included in the original Japanese publication.]

Seikyo Shimbun: Today, we live in a world confronted by a host of pressing challenges: armed conflicts, human rights violations, the rise of far-right movements and financial market instability. How do you see the current global situation, and what do you believe lies at the heart of these challenges?

Prof. Stuart Rees

Prof. Stuart Rees: In many parts of the world, we see that ethical standards are deteriorating. Everything seems to come down to self-interest—every person, or every nation, looking out only for themselves. Inequality is one of the main drivers of instability. But I don’t believe the problem is purely economic. There’s a deeper cultural issue at play, ones that distort our views, making us believe that power means dominance, and that success is about having more—more wealth, more weapons, more control. This mindset encourages competition over cooperation, and it shapes how we speak, behave and treat each other.

I often say that there are two kinds of power. One is coercive, which aims to dominate or suppress. The other is life-enhancing, which seeks to protect dignity, foster solidarity and support people in leading meaningful lives. The problem is, we see too much of the former and not nearly enough of the latter. That’s why I continue to insist that peace must be grounded in justice.

Seikyo: Peace based on justice is an idea you have long emphasized. Could you explain what this means and why it is such a vital foundation for lasting peace?

Rees: You can’t have peace if people are being silenced or if their basic needs and rights are ignored. Real peace goes beyond the absence of war.

It must serve as a foundation that enhances your life mentally, physically, culturally and spiritually. That’s the kind of peace worth working toward. Justice presupposes a statement about the quality of our lives. Do you have access to good education? Do you have access to good healthcare? Do you have access to productive employment? Do you live in a non-discriminating world? These are the true components of peace. Hence, it is not merely the absence of violence, but peace grounded in justice.

Peace without justice is, in a sense, built on sand. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, halted the gunfire and bloodshed and brought a semblance of peace. However, because its terms were punitive and unjust, it ultimately sowed the seeds of the next war. The values were inadequate, and so was the language.

In contrast, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, created in the aftermath of two world wars, is a clear example of life-enhancing power—a global statement that symbolizes and affirms the inherent dignity and equality of all people. At a time when authoritarianism is on the rise and societies are becoming more divided, we need that kind of shared ethic more than ever.

Seikyo: In our divided world, the effort to communicate across differences has never been more crucial. Yet, how can we restore dignity and build connections in situations where dialogue seems impossible?

Rees: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, comprising 30 articles, affirms the dignity of every human being, regardless of race, gender, religion or other differences. It precisely articulates the spirit of dialogue—a language of non-violence meant to overcome division and discrimination.

In my experience, meaningful dialogue—especially when conflict runs deep—begins not with argument, but with respect. That may seem obvious, but it’s not always easy when you are facing someone whose views are profoundly different. Everything begins with recognizing the dignity of the person in front of you.

I’ve been in parts of Africa or the Middle East where tensions run high, and met with military leaders, who likely did not expect dialogue to be possible. I began asking questions like, “General, what kind of music do you enjoy?” or “How many children do you have?” These questions opened up a basic human connection. I call it the promise of biography. Once you know something about someone’s story, it becomes harder to reduce them to a title or role.

That’s why I’m critical of foreign policies built on humiliation or exclusion. When has forcing people into a corner and refusing to communicate with them ever resulted in peace? When has anyone ever said, “Thank you for humiliating me. I’ll now change completely and become what you want”? People respond to sincerity. When they feel respected—when they sense they are being taken seriously—they are most likely to want to respond in kind.

This reminds me of a quote often attributed to the French writer and philosopher Voltaire: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” That, to me, captures the spirit of dialogue—not agreeing with everything, but believing that people must be heard.

I’m one of the few Westerners who have sat down with the leaders of Hamas. We talked about the structure of government. We talked about the status of women. Admittedly, it was through an interpreter—I don’t speak Arabic. But during that hour, there was a real sense of connection. They are human beings, just like you and I. At its best, dialogue isn’t just about exchanging information—it’s about feeling. It’s about asking, “What inspires you? Is it a piece of music? A style of architecture? A favorite dish?” These aren’t side questions. They are the very fabric of human connection. And yes, humor matters too. Humor, when it’s not cruel, invites a moment of shared insight. It can shift the energy in the room.

Seikyo: A key to cultivating connection across differences is whether we ourselves can become someone who can respect others. This inner transformation—turning the focus inward—was also a recurring theme in your discussions with Mr. Ikeda.

Rees: One of the major challenges in today’s world is that many of us are constantly on the run—as if life were a competition for stamina or material success. In such a lifestyle, it becomes increasingly difficult to pause and reflect on ourselves. But reflection is essential. Trouble begins the moment we think we have all the answers or believe we’re above criticism. So, I always say: humility is the foundation. Without it, there’s no space for growth or peace. Inner transformation begins with the willingness to pause and recognize how little we truly know.

That’s where I see a strong parallel with President Ikeda’s message. His writings and leadership have consistently emphasized that lasting peace begins in the heart. It’s about transforming how we see ourselves and others—not as adversaries, but as fellow human beings. That shift takes courage and imagination.

I also believe that true education fosters that kind of inner change. It’s not just about credentials or efficiency. It’s about empathy, awareness and character. I’ve seen this approach in the Soka schools in Japan, as well as at Soka University campuses in Japan and the United States. These aren’t just places for formal learning. They are spaces where music, art, dialogue, and joy are cultivated. What I would call a nonviolent language of culture.

President Ikeda’s initiatives—from poetry collections to music libraries to museums—reflect a belief that education is a lifelong, humanistic pursuit. And I think that’s the real goal of education: not just to give knowledge, but to inspire a sense of responsibility. To ask not only “How do I succeed?” but also “How do I contribute to a more humane world?”

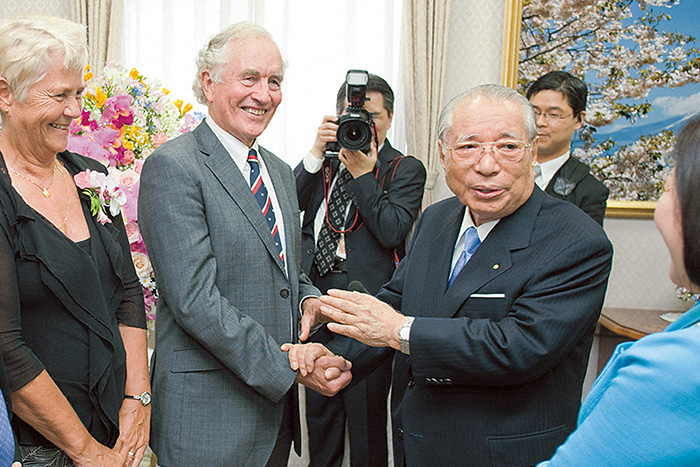

Seikyo: You met with Mr. Ikeda on four occasions and coauthored the dialogue Peace, Justice, and the Poetic Mind: Conversations on the Path of Nonviolence. How would you assess his contributions to peace?

Rees: When I had the opportunity to meet President Ikeda, it was a privilege. I was meeting an absolutely fascinating human being, with a poetic mind that wove together justice, love, the arts and humanity—like a tapestry. There was a kind of chemistry in our conversations—something that spoke not only to reason, but to imagination and to conscience.

There is a famous quote by the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley: “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” What he meant is that artists illuminate what truly matters to humanity, awaken empathy, and expand our moral horizon. President Ikeda deeply understood this. His vision of peace was inseparable from poetry, the arts, and the emotional richness of everyday life.

Not everyone may connect with poetry in the traditional sense, but its spirit can be found in how we live, speak and care for others. You don’t need to write poetry to live poetically. It can manifest in everyday acts of generosity, the warmth of hospitality, or the courage to help strangers in times of adversities. Even policies like universal health insurance, which extend care to people we may never meet, reflect a kind of poetry—a spirit of compassion that transcends familiarity. This kind of poetry is lived: it’s multidimensional, curious and willing to see beyond the predictable.

SGI has a history of moral courage. Its three presidents—Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, Josei Toda and Daisaku Ikeda—stood firm in their beliefs and faced persecution. Makiguchi was even imprisoned and died for resisting militarism of his time. That takes conviction and it’s something we rarely see today. There has to be courage in public life. It’s often a quality that is absent. Too many leaders wait to see which way the wind blows. They avoid risk. But conscience isn’t something to be outsourced. It has to be lived.

When I think about President Ikeda’s legacy, I think first of his contribution to peace, especially his steadfast advocacy for nuclear abolition, which is deeply humane. He appealed not just to institutions but reached out to ordinary citizens, fostering public awareness and solidarity.

He also held profound faith in the role of the United Nations—not as a perfect institution, but as an essential platform for promoting dialogue and cooperation. He was also deeply engaged with the issue of climate change, recognizing it as the defining challenge for the future of humanity. For him, the need to protect and preserve our precious natural environment was not just a matter of science or politics—it was ultimately an ethical responsibility, rooted in our shared humanity.

In my own work, I’ve spent time with Indigenous communities. I’ve learned from their belief that the environment isn’t separate from us—it’s part of who we are. That idea—of interconnectedness—resonates with Buddhist thought, and with President Ikeda’s message. It’s not about control. It’s about stewardship and shared responsibility.

President Ikeda dedicated his life to building a peace grounded in justice. I believe that each of his efforts stands as a spiritual legacy that will shine in the annals of human history.

Seikyo: The Soka Gakkai has long placed grassroots dialogue at the heart of its peace movement. From your perspective, how do you view the organization’s ongoing commitment to peace and its role in today’s global context?

A local SGI Australia discussion meeting (Melbourne, November 2023)

Rees: I’ve always admired the cultural dimension of the Soka Gakkai’s work. The meetings are more than just places for dialogue. There’s music, poetry and joy. This, to me, is the very language of peace. And President Ikeda understood that deeply. He saw that peace isn’t just the absence of war. It’s the presence of culture, creativity and conscience.

And I’m encouraged, too, by the young people I meet in Soka Gakkai—they are full of hope and aspiration. That gives me confidence in the future.

In a time marked by conflict and division, this kind of moral community offers something different: a quiet strength, a literacy of nonviolence, and a reminder that the most lasting change often begins in the smallest places—between two people, in conversation, or over a shared meal—and grows outward from there.

Seikyo: You’ve often emphasized the importance of connection and shared purpose. How do you see small groups and communities bringing about social transformation?

Rees: I’m often asked by students, “What can I do?” And I usually say, “I’m not sure you can do much on your own. But working together with one or two others, you can do a lot.” Of course, realizing meaningful change, requires a clear vision and a sense of purpose. But it all begins with small conversations and a little courage.

The first step toward change is overcoming fatalism—that sense of resignation that nothing we will do will make a difference. I feel it too, especially when I reflect on the tragedies unfolding in the Middle East today. But if we let that feeling take over, even getting out of bed in the morning can feel impossible. That’s why we search for hope every day—even if it comes in the form of the smallest victory.

In that sense, community provides enormous support. When I was a director of the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney, we had students from all over the world. And even in serious work, we found joy. That’s important. I often say: any movement worth building must also be enjoyable. If it doesn’t bring connection and energy, it won’t last. That’s also what I’ve seen at Soka Gakkai gatherings. There’s music, food and hospitality. It’s not superficial. It’s a culture that lifts people up. Soka Gakkai is not just a group of like-minded individuals. It’s a moral community—people who live their values and support each other to act on them.

These kinds of small group conversations—like the one we’re having right now—are happening all over Soka Gakkai communities around the world. And they matter. And it doesn’t stop at the local level. What begins in friendship often grows into global responsibility.

President Ikeda engaged in dialogue around the world, bringing together thinkers, artists and activists across cultures and ideologies. He showed us how powerful dialogue grounded in mutual respect can be. It’s a legacy that will continue to offer deep inspiration long into the future.

Stuart Rees is Professor Emeritus at the University of Sydney and former director of the Sydney Peace Foundation. Born in England in 1939, he has been involved in humanitarian and social welfare work in various countries, including Great Britain, Canada, India and Sri Lanka. He is also the founding director of the Centre for Peace & Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney, a position he held for eighteen years. His notable works include Human Rights, Corporate Responsibility: A Dialogue, Passion for Peace: Exercising Power Creatively,” and the poetry anthology Tell Me the Truth About War. In 2005, he was awarded the Order of Australia for his contributions to international relations.

Share this page