A Mentor for Humanity: Daisaku Ikeda’s Global Legacy

[The following is excerpted from an interview with Dr. Lawrence Edward Carter Sr., conducted by the Seikyo Shimbun and published in the paper on July 12, 2024. In this interview, Dr. Lawrence E. Carter Sr., a Baptist minister, reflects on his encounters with SGI President Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023) and shares insights on how humanity can unite and work together for peace, regardless of differences in nationality, ethnicity or religion.]

Seikyo Shimbun: You’ve dedicated yourself to organizing the “Gandhi, King, Ikeda: A Legacy of Building Peace” exhibitions around the world and have long worked to promote the shared philosophy and practice of nonviolence advocated by these three leaders. Yet even today, violence persists in the form of war, discrimination and inequality. What are your thoughts on the challenges we face?

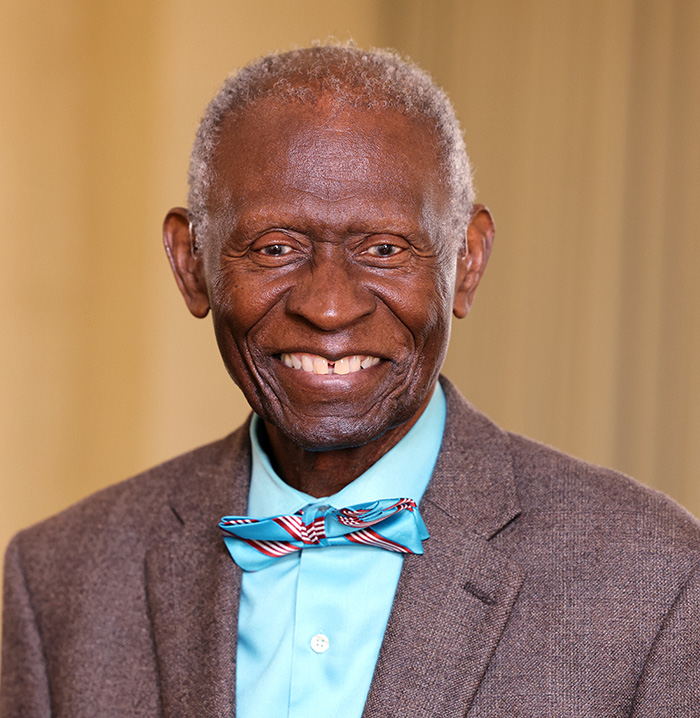

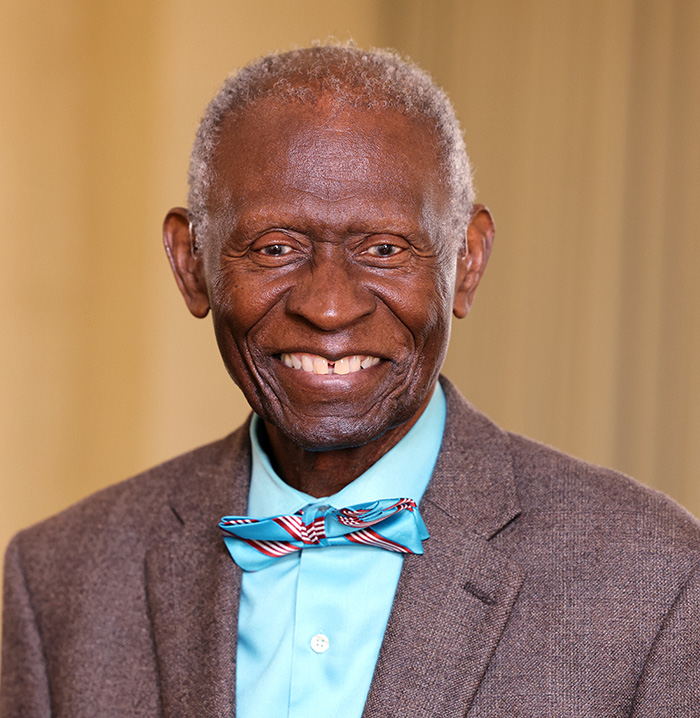

Dr. Lawrence E. Carter Sr., founding dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel Morehouse College

Dr. Lawrence E. Carter Sr.: The crises unfolding all around the world are deeply interconnected, marked by a high degree of intersectionality—the way multiple forms of discrimination and inequality interact. In other words, none of these issues can be reduced to a single-issue perspective. What we are witnessing today, including the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, stands in stark contrast to the ideals and teachings upheld by Nichiren Buddhism and Christianity. I believe most religions share, at their core, the same perspective as Nichiren Buddhism—namely, the affirmation of humanity and each person just as they are.

This affirmation was the strongest instruction and legacy that second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda entrusted to Dr. Ikeda. As his final message, President Toda issued the “Declaration Calling for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons,” in which he denounced the use of nuclear weapons as the greatest evil—even referring to it as devils—to assert the supreme dignity of life. This affirmation of the sacredness of life is also foundational to the teachings of Jesus. Nothing surpasses life in dignity and wholeness—it must never be violated.

Building on that legacy, at the heart of Dr. Ikeda’s unprecedented movement for kosen-rufu (world peace through individual happiness) is a profound reverence for the sanctity of life. I interpret it to mean the realization of peace, the effort to remove suffering and bring joy. Central to this is the Gohonzon, which unlocks the limitless potential inherent in each individual’s life.

Peace is the wholeness of right relationships—first with the self, then with others, the community, the environment, and ultimately the universe. Peace is the state in which these relationships exist in harmony and balance.

Seikyo: In your book, A Baptist Preacher’s Buddhist Teacher, you reflect on your encounters with Mr. Ikeda, expressing profound hope in the Soka Gakkai’s philosophy and practice.

Carter: I first heard about Dr. Ikeda through an SGI-USA[1] member who was also a professor at Clark Atlanta University. At the time, I was deeply questioning whether I could truly fulfill my mission as Dean of the King Chapel. She introduced me to the Soka Gakkai, and as I began reading Dr. Ikeda’s writings, I was stunned. I was deeply moved to discover someone who so fully embodied the philosophy and practice of nonviolence, the very path I had been striving to follow as a disciple of Martin Luther King Jr.

What impressed me most as I studied his work and deepened my interactions with SGI-USA members were the striking similarities shared by Dr. Ikeda, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Dr. King. Gandhi, a devout Hindu, had studied the teachings of Leo Tolstoy, the Russian novelist and proponent of nonviolent pacifism. King said that it was Jesus who led him to Gandhi. Nelson Mandela, too, drew on Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence in his struggle against social injustice in South Africa. Likewise, Dr. Ikeda traveled the world, engaging in dialogue with people from all walks of life in pursuit of peace.

Dr. Ikeda had a natural ability to connect with people of diverse religious and cultural backgrounds. Like King, he exemplified the essence of a humanitarian global citizen—someone who sees beyond ethnicity and nationality and respects each individual as a member of one shared humanity. He transcended boundaries of nation, culture, race and economy. Gandhi, King and Ikeda each broke through the entrenched barriers of their time to connect people across all divides.

Further, Dr. Ikeda also engaged in profound, wisdom-filled interdisciplinary dialogues with scholars, leaders, and thinkers worldwide, resulting in numerous books and collaborative works. He was not merely a preacher or proponent, but a man of action. Through the power of dialogue and the written word, Dr. Ikeda expanded the Soka Gakkai into a global movement that now has more than 12 million members in 192 countries and territories.

As a Baptist minister, I chose Dr. King as my mentor over half a century ago and Gandhi more than 30 years ago. When I learned about Dr. Ikeda’s noble undertakings, I met my third mentor—one of truly global stature.

The subtitle of my book, A Baptist Preacher’s Buddhist Teacher, reads: How My Interfaith Journey With Daisaku Ikeda Made Me a Better Christian. I had long grappled with how best to preserve and carry forward Dr. King’s legacy of nonviolence. In Nichiren Buddhism, I found an answer to that prayer.

Seikyo: Mr. Ikeda once wrote, “The Lotus Sutra, the monarch of all scriptures, embodies a fundamental humanism in which people are the end, not the means, where people are the protagonists, the monarchs.” Based on this universal humanism embedded in Buddhism, the Soka Gakkai has consistently upheld the practice of treasuring each individual in every corner of the world.

Carter: The dignity of every human being must be respected. Only then can we truly regard one another as neighbors and learn to live together in harmony. Otherwise, we will perish as fools. We must learn to engage in respectful disagreement without diminishing the humanity of others.

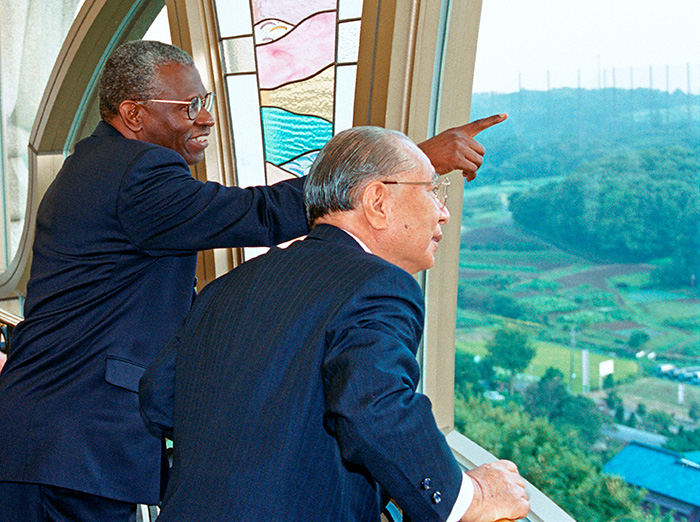

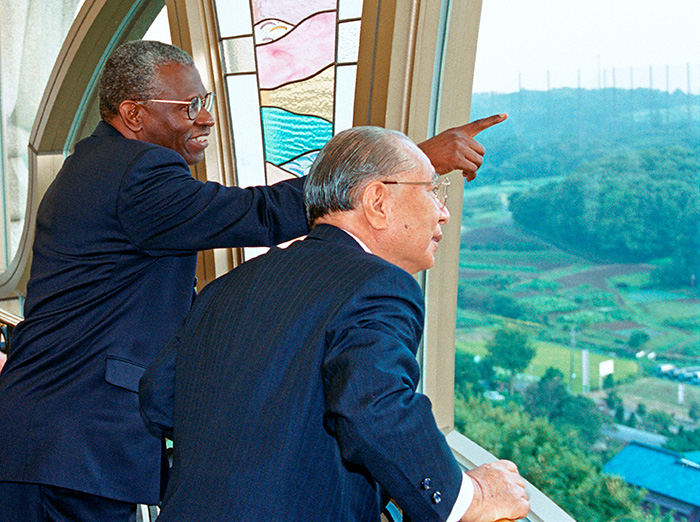

Daisaku Ikeda taking in the view from a window at the Makiguchi Memorial Hall with Lawrence E. Carter Sr., founding dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel (Tokyo, September 2000)

Dr. Ikeda left us with a blueprint for transcending all boundaries and uniting people across differences. This is possible because Nichiren Buddhism does not confine individuals to a single category or identity; instead, it recognizes and embraces each person for who they truly are.

One of the most distinctive characteristics of the Soka Gakkai is its emphasis on “discussion meetings” at the core of its activities. Though modest in appearance, these small gatherings, in my view, embody the spirit of egalitarianism embedded in the very foundation of the Soka Gakkai. It is a faith-based community that seeks the happiness and enlightenment of all people, grounded in an absolute affirmation of each individual.

When we remove the divisions of nationality, race, ethnicity, gender, culture, economics, language and education, what emerges is our shared foundation—our identity as human beings. Gandhi described it as a “global village.” King envisioned it as “the world house.” Mandela called for a “solidarity of peace-loving nations.” Dr. Ikeda realized these ideals through the Soka Gakkai, a “community of global citizens.”

If we are to become moral cosmopolitans—those who view humanity as one—we must strive to live as global citizens. Dr. Ikeda consistently emphasized the importance of living as universal citizens. This principle is rooted in the legacy of the Soka Gakkai’s first and second presidents, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and Josei Toda, whose spirit continues to be upheld within the organization.

This means embracing a greater “address” in life—one that goes beyond the house or street where we reside and extends to our community, society and the world. Such a broader address must also reflect our interconnectedness with the local community, society, the world and, ultimately, the universe.

The crisis we face today is not “national warming” but “global warming.” The challenges of our time can’t be confined within the borders of any one country or region. For example, climate change is intricately interconnected with other global issues, affecting ecosystems and economies throughout the world.

From the time Dr. Ikeda assumed the presidency of the Soka Gakkai in 1960 to the year 2024, much has changed. In recent years alone, we have lived through a global pandemic and the escalating threat of climate change—crises that have made clear the need for an even greater “address” in life. I believe Dr. Ikeda expanded our view of the world and proposed a way of life as cosmic citizens.

Seikyo: Mr. Ikeda once stated that opening our eyes to the universe leads to a deeper understanding of what it means to be human, and to awaken to our identity as citizens of the Earth. He also remarked that from the perspective of the universe, Earth is truly one home, and all of humanity is part of the same global community. In your opinion, what is required of us as we move into what could be called the “space age?”

Carter: We cannot shoulder the responsibility of addressing the global crisis without adopting a broader, cosmic perspective. Losing our connection with the natural environment means losing touch with our true selves. In today’s society, where people struggle to see the connection between the environment and their personal identities, what is required is an awareness as cosmic citizens.

For me, Dr. Ikeda is a model of a cosmic citizen. In today’s age, what we need most is the spirit of inclusion he embodied—the willingness to engage in dialogue with people of varied backgrounds, build international relationships and respect differences and diversity.

Dr. Ikeda passed away last year (2023). Throughout his life, he emphasized that the future belongs to the youth and repeatedly stressed the vital importance of fostering the next generation. He also encouraged the members to have the awareness that “I am Soka Gakkai.”

Jesus did not wish to be worshipped after his death; instead, he hoped his actions would serve as a model for his disciples to follow. Neither Presidents Makiguchi, Toda, Ikeda, nor the Buddha or Muhammad sought veneration.

When I came to Morehouse College in 1979, the first thing I requested was to rename the “King Memorial Chapel” the “King International Chapel.” While many people admired and revered Dr. King, I questioned how many were truly living out his ideals. I wanted the chapel to serve as more than just a monument or a museum dedicated to past struggles. Rather, I envisioned it as a place for active reflection and engagement with the global issues confronting humanity today.

Dr. Ikeda is truly an inspiring role model. But we should not be content with merely admiring his legacy. Just as Dr. Ikeda encouraged Soka Gakkai members to recognize their own agency, each of you is a newly awakened human being (a Buddha), and as a new Bodhisattva, you must take action for the sake of humanity.

Earlier, I spoke of Dr. Ikeda’s writings—the power of his pen. The emblems of Soka University and Soka University of America, both founded by him, depict the nib of a fountain pen. Over the years, Dr. Ikeda authored countless works, coauthored dialogues with global leaders and published numerous peace proposals.

I believe that many of you will continue to read and study Dr. Ikeda’s writings on global peace. A distinctive feature of his work is that he avoided overly flowery or elaborate language—his writing was clear, sincere and accessible so that anyone could understand. His writings serve as both a roadmap and a compass. As long as you continue to read and learn from them, you will never lose your way.

Dr. Ikeda also consistently emphasized the role of the United Nations and its mission to achieve lasting global peace. The concept of kosen-rufu in Nichiren Buddhism is fundamentally aligned with the pursuit of that peace. In this context, the everyday activities of Soka Gakkai members embody the UN’s highest ideals at a local, grassroots level. In this sense, I see every Soka Gakkai community center as something akin to a local “UN headquarters.”

Let us continue to follow Dr. Ikeda’s example and work together to build peace. What matters most is that each of you takes action—in your daily life, in your community and on the global stage—to realize this vision.

Lawrence Edward Carter Sr. is the founding dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse College and a professor of religion at the college. He was born in Dawson, Georgia, USA, in 1941. Dr. Carter holds an M. Div. degree in Theology, an S.T.M. degree in pastoral care, and a Ph.D. in pastoral psychology and counseling from Boston University. He is also a Baptist minister. Throughout his life, Dr. Carter has devoted his life to advancing Dr. King’s vision of peace and justice through a wide range of educational initiatives, including lectures at universities and seminars around the world. He also serves on the Board of Trustees at Soka University of America, reflecting his commitment to interfaith dialogue and global education. Among his published works are Walking Integrity: Benjamin Elijah Mays as Mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. and A Baptist Preacher’s Buddhist Teacher.

Share this page